My previous post was about how I think copy-on-write is the future of concurrent programming. The next day, I was trying to explain the idea to a couple of colleagues but got just blank stares in return. It struck me that most programmers don’t really know much about copy-on-write techniques, how (or even if) they work, and what kinds of problems they’re best suited for. So, I’ve decided to write a small series of posts on this subject. In this first post, I’ll explain the basic idea of copy-on-write data structures.

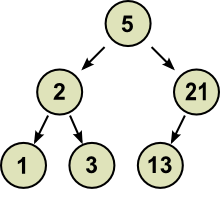

Traditional data structures are mutable. Let’s look at a simple binary search tree, for example:

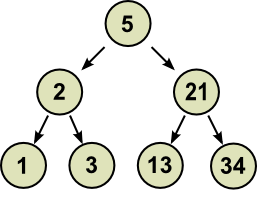

Each node in the tree consists of a value (the number) and zero, one, or two arrows pointing to other nodes. Say you want to add a new node, a 34, in this tree. That’s easy, we just draw the new node in the right place:

Note that the tree is now changed. We had to update node 21 to point to node 34 in addition to 13. The original tree for all practical purposes does not exist anymore. Well, OK, it does on this page right here, but you get the point. At any one time, there is exactly one version of the tree in existence in your program.

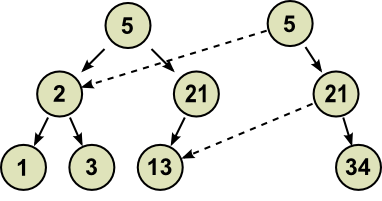

A copy-on-write data structure, on the other hand, is immutable. Once you have gone and created a binary tree, you can never ever change it. Adding an arrow from 21 to 34 is not allowed, no sir, over here in the wacky world of copy-on-write you have to create a modified copy instead of actually modifying anything.

If having to copy the entire tree seems a little bit ridiculous to you, that’s because it probably is. Typically, two trees are considered equal if they represent the same structure. Hence, it does not matter where the nodes of the tree are stored in memory, for example. In fact, in many programming languages there is even no way to distinguish between two copies of otherwise identical pieces of data. With this in mind, we can share structure instead of taking a full copy:

Here we have both the old tree (without the 34) and the new tree (including the 34). An application will be looking at this data through a window that is the programming language, and all it sees are the two completely separate versions of the tree. They happen to share some structure, but that arguably does not matter much to the application.

In general, if you’re updating one node, taking a modified copy of a tree will require copying only the path from the root node of the tree to the affected node. And that’s how copy-on-write trees work: path copying. Tah-dah!

It is not immediately clear if a structure-sharing copy-on-write counterpart can be created for all mutable data structures. All tree-like structures can clearly be handled with the path copying trick. Other structures, such as queues, seem harder, perhaps impossible at first glance.

Luckily, it turns out that smart people have already designed efficient copy-on-write versions of queues and many other important data structures; there’s a great book on the subject by Chris Okasaki called Purely Functional Data Structures. It’s by far the best resource on copy-on-write data structures that I’ve encountered.

Luckily, it turns out that smart people have already designed efficient copy-on-write versions of queues and many other important data structures; there’s a great book on the subject by Chris Okasaki called Purely Functional Data Structures. It’s by far the best resource on copy-on-write data structures that I’ve encountered.

Note how I prefer to say “copy-on-write” instead of “purely functional”. The term “functional” is just way too overloaded and carries a lot of negative connotations in the minds of working programmers who don’t much care for many of the things that functional programming is often associated with.

The use of copy-on-write data structures is not limited to functional programming, so let’s not marry the two by calling them with the same name.

Copy-on-write data structures are also sometimes called “persistent” data structures, because the old versions are preserved; they “persist” in memory. In practice, this is easily confused with persistent storage (e.g. disk), so I avoid using that name as well.

Next: Copy-on-write 101 – Part 2: Putting it to use

Related posts:

- Copy-On-Write 101 – Part 2: Putting It to Use

- I Have Seen the Future, and It is Copy-On-Write

- Copy-On-Write 101 – Part 3: The Sum of Its Parts

If you liked this, click here to receive new posts in a reader.

You should also follow me on Twitter here.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 comment }

Excellent description, don’t stop there though, ZFS needs you.

{ 1 trackback }